While not the ‘Great Resignation’, there’s been an uptick in Australians switching jobs

The past year has been awash with suggestions countries such as Australia are experiencing a “great resignation” as workers previously loyal to their employers quit their jobs and look for others elsewhere.

Last year, newspaper articles aside, there was little evidence for this in Australia, although substantial evidence in the United States where the term came from.

In the US, so-called “quit rates” hit a record high in 2021, while in Australia the proportion of workers switching jobs fell to its lowest point in half a century.

Writing in November, University of Melbourne economists Mark Wooden and Peter Gahan pointed out that in the US, COVID-19 had made public-facing jobs unsafe, which may have contributed to people quitting these roles en masse.

Quit rates hadn’t climbed in US finance or information technology jobs.

In Australia, where border closures, mask mandates and vaccination mandates made public-facing jobs safer, job-switching continued its long-term decline.

Until now. The annual February mobility survey published by the Bureau of Statistics in May shows an uptick in the proportion of workers switching, from a record low of 7.5% to 9.5%.

One way to look at the uptick is to say Australia has the highest switching rate since 2012. If records only went back to 2012, we could say Australia had the highest switching rate on record.

But here’s the thing. The US records only go back to December 2000. If they went back further, US quit rates might be seen to be on the same sort of long-term slide as Australia’s. We just don’t know.

In Australia’s case, recent job mobility rates over the last decade or two have been extraordinarily low compared to historical job mobility levels. For all we know this is the case in the US as well.

At one point the late 1980s, almost one in five Australian workers changed jobs in a year. These days, even after the latest uptick, it is one in 10.

The uptick might be little more than a rebound from a specific historic low caused by lockdowns and border closures.

We can be sure that the uptick in job switching is not due to an uptick in retrenchments. Australia’s retrenchment rate (the number of people who are retrenched in a year as a proportion of the number employed at the start of that year) fell to a 50-year low in February.

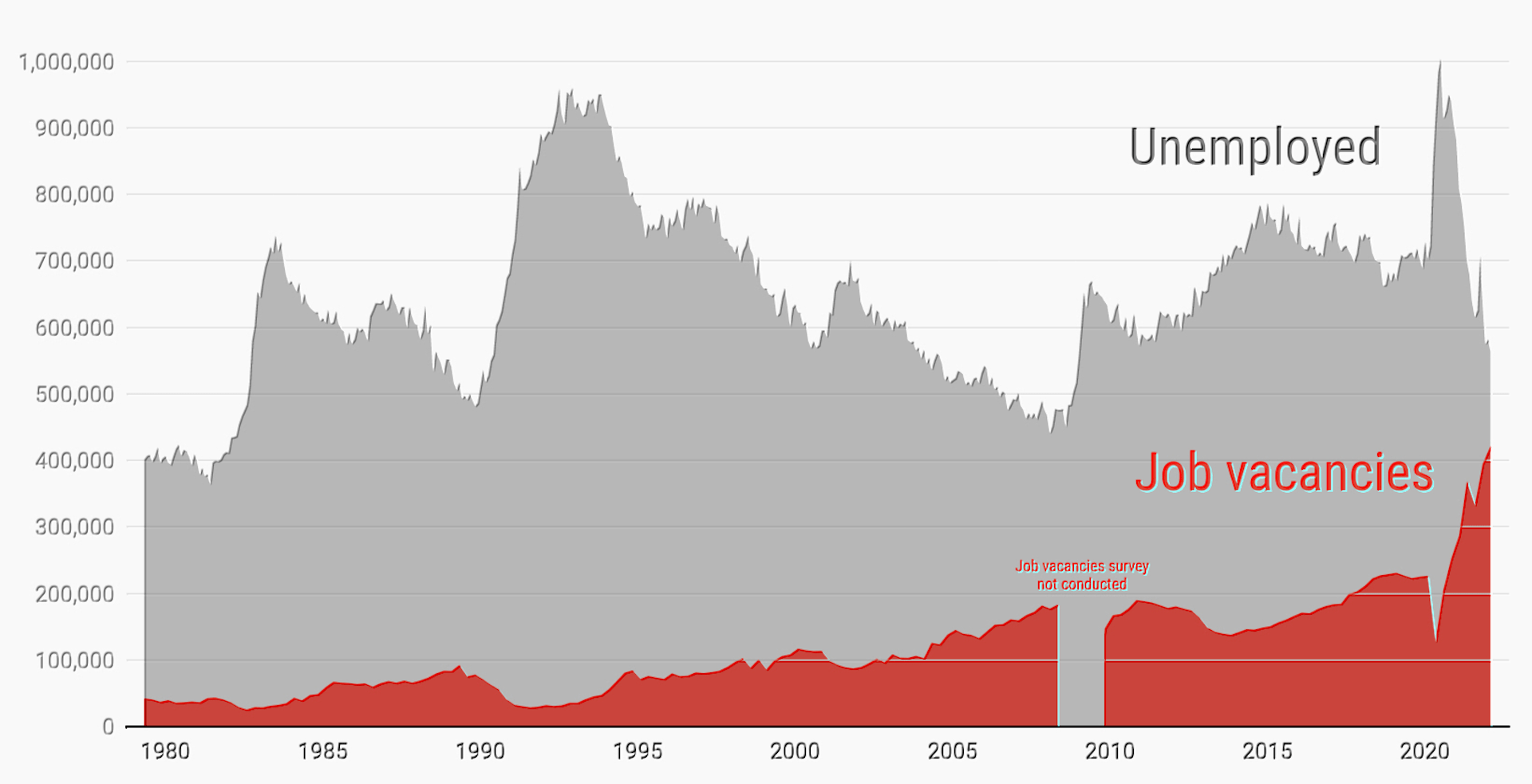

Another thing we know is that there are more job vacancies (and more job vacancies per unemployed persons) than ever before in Australia.

There were 423,500 unfilled jobs in February, and 563,300 unemployed, meaning there were only 1.3 unemployed people chasing each vacant job, the slowest ratio in records going back to 1980.

More job vacancies for each unemployed person than ever before

This is likely to mean that more people will be tempted to switch jobs soon.

They might even be doing it, meaning the uptick will continue when the figures are updated next February. Watch this space.![]()

Martin Edwards is an Associate Professor in management and business from The University of Queensland.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.